Why you need an Scientific Illustrator? Well, because the sketch on the left would be the limit for me! Sketch and final artwork of DNA created by Philipp Dexheimer © Philipp Dexheimer

How did you get into your profession? What was your first project/commission and how did you get it?

Joana C. Carvalho works as a full-time science illustrator and designer since 2020. She holds a Master in Evolutionary and Developmental Biology and is currently enrolled in a Master in Communication of Science and Innovation. Recently she has been enjoying experimenting with mixing 2D and 3D in her illustrations. You can find out more about her on her website.

Joana: Hello everyone! My career path began with research in the life sciences and later led me into scientific visualization. I started my studies with a bachelor in Biology, followed by an internship where I studied cell polarity in plants, and then a masters in evolutionary and developmental biology, where I studied the immune system of the fruit fly.

Although I had had contact with scientific visualization early on during my studies, in classes and in the books I read, it was not until I started working on an actual research project that I realized its potential. I worked for a few years as a research technician after graduating and some of the most exciting opportunities I had during that period happened when I had to communicate my research. I became deeply curious about how I could use design and visual communication principles to support and enhance posters, figures, or presentations.

By the end of my time working in the lab, I had completed a few courses, developed a lot of self-taught skills and worked on enough volunteer projects to feel confident to assemble a portfolio. The support from my colleagues, including the head of the lab where I was working at the time, were significant for me to move in this direction.

I paired my first portfolio with a job proposal, presented it to the director of the research institute where I was working at, and was given the incredible opportunity to join the institutional communications team. My first tasks on the job delivered a few editorial illustrations to highlight new research from the different labs at the institute. Afterwards, my role expanded, not just in terms of the applications of illustration, but also in making use of graphic design to apply the institute’s visual identity in a variety of formats.

In parallel to this, I opened my own business, which I later on launched as a full-time job. This allowed me to start taking on commissions from researchers outside of my home institute and keep expanding my skills. The first commission that came in was a banner for a website done in watercolor, focusing on the topic of motor proteins and their structure. At the time, this was the result of some social media marketing and a network of incredibly supportive colleagues that my years as a researcher allowed me to build.

Was your job proposal for a open job vacancy or did you took the initiative and did a speculative job application?

Yes, my approach at the time was a type of speculative job application. The institute where I was working was quite unique in their collective awareness of the impact of visuals in institutional communication and outreach. There was a fantastic culture of encouragement and support towards science and art collaborations, which I think made my application smoother.

This speculative job application was an interesting strategy exercise. Looking back, I would have done it completely different with the knowledge I have today. I was not even aware this was an option to start with, but now realize these lateral career movements are more common than one might assume.

My PI at the time was the one suggesting me to consider this and he really helped me make the first contact with the direction board. Another thing that was very helpful from my perspective was having some project examples ready to support the proposal.

Philipp: Hi everyone! I always loved nature and decided to study Biology and Biochemistry after school. Back then, I was already an active painter, doing mostly graffiti on walls and occasionally sketching various motifs for fun using pen and paper. However, my artistic interest in Molecular Biology only emerged after I started my PhD in Life Sciences.

Microscopy was always one of my favorite tasks in the lab. The microcosmos comes with a unique set of aesthetics, and I was always fascinated by the beauty of my samples when imaging cells or developing embryos. So it didn’t take long until I started taking inspiration for my artwork from the objects and concepts I encountered in the lab on a daily basis. Artists spent centuries, if not millennia, representing the macromolecular world in their works. The microcosmos is much less explored, mostly owing to the fact that we were unaware of it until fairly recently in historical terms. My long-term vision as an artist is to change that and explore the microscopic world in my creations.

What started as a passion project for fun quickly turned into a side job during my PhD and Postdoc. In the beginning, it was mostly friends or collaborators who asked me to illustrate their scientific discoveries, and I was always happy to venture into new artistic projects.

My first professional commission was a cover illustration for EMBO Journal, and from then on more and more projects kept coming in.

Last year, I decided to leave academia for good and go all-in with Science Art. Since then, I have worked as a full-time freelancer, doing mostly cover designs, illustrations for papers and presentations, as well as animations explaining complex concepts in engaging and accessible ways.

How exactly did you get your first professional commission. Did a colleague just asked and offered to pay?

In the beginning I was just happy to create and did not actually consider myself a professional that charges for the service. At some point a PI at our Institute asked me if I want to design a header for their lab homepage and how much it would cost them – this was the moment I realized that my work is worth actual money. My initial hourly rate was ridiculously low, and it actually took me quite a while to built up the professional self confidence to charge an appropriate compensation without feeling weird about it, I guess you could call it the creative’s imposter syndrome. My advice to people who want to start a career as an illustrator: Don’t hesitate to charge a healthy rate – it’s fair and will actually motivate you to deliver even better results!

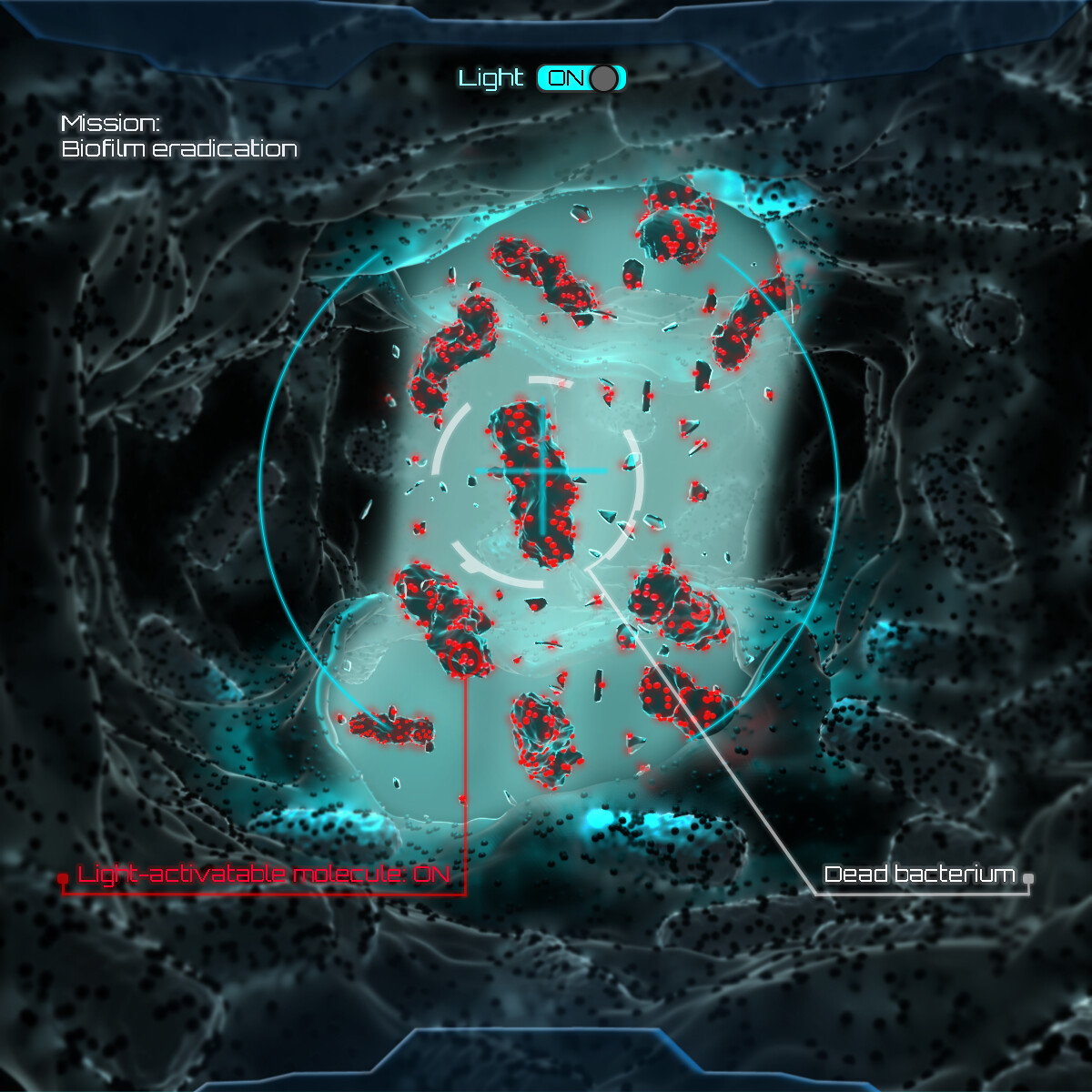

Patricia: Hi everyone, I am very happy to get to know a bit more about you. I felt quite identified with your stories. My journey into scientific illustration started during my PhD. I was also inspired by microscopy and the beauty of biological structures. In fact, my thesis focused on combining different microscopy techniques to approach samples from complementary perspectives. However, when I tried to communicate my work in congresses and talks, I realized how difficult it was for me to connect with the audience.

To address this, I started creating illustrations to support my explanations and help the audience understand my work. I found this process very inspiring and wanted to go deeper, so I studied a 2-year technical course on 3D animation and video games while continuing with my lab work. Through this course, I learned to use various graphical tools and entered the audiovisual world, which I found fascinating. This was a turning point for me, as it made me realize the potential of visual communication for conveying scientific concepts and sparking interest and curiosity about STEM areas in society.

My first significant project was creating a cover illustration for one of my thesis papers. I poured a lot of effort into making it visually compelling and informative, and to my delight, it was chosen by the journal. This success was a huge confidence boost for me.

Encouraged by this experience, I started sharing my illustrations on social media while expanding my portfolio by creating illustrations for my peers. As my work gained visibility, people outside my immediate network began noticing my illustrations. My first commissioned work was a cover for a scientist who connected with me through LinkedIn and hired me to create a journal cover. This was my first professional experience as a scientific illustrator and proved to me that it was possible to make a living from this profession.

As Philipp mentioned, I also found myself charging a very low rate per hour at the beginning. It took me some time to feel confident enough to ask for a fair rate, but this was an important step in establishing myself. It also helped a lot to ask for advice from other professionals.

Composition of five illustration work examples done by Joana Carvalho, covering fields like the origin of life, cancer immunity, algal biotechnology, blood coagulation disorders and neuroscience. © Joana C. Carvalho

How did you learn to draw scientific illustrations? How do you practice, what are your tips?

Philipp Dexheimer works as a science artist since 2017. He holds a PhD in Genetics. His favourite artstyles include spraypainting molecular Graffiti, digital illustrations, and drawing with Ink & watercolor. You can find more about him on his website.

Philipp: To me there are two elements required for mastering scientific illustrations: the technical aspect of using a specific medium and developing visual literacy to get a feeling for design principles like color theory and layout.

On the technical side, my main tools are Adobe Photoshop & Illustrator, which are complemented by a variety of other software for the more specialized tasks. When starting scientific illustrations I had zero practice with digital tools and for me self-teaching was the way to go. In most cases the initial steps with complicated software like Adobe can be quite frustrating. However, once you become familiar with the programs, it’s easy to learn how to do more sophisticated operations with the help of online tutorials. My preferred way of learning how to use new tools and techniques is to take on a project that requires me to learn them. When faced with the challenge to illustrate a complex concept I often have a solution in mind which I cannot technically create yet, so I need to figure out how to get there in the course of the project. Coupled with a high aim for quality, this is a great way to improve skills and becoming proficient in the craft.

To develop a strong sense of visual literacy there are some amazing books out there. I can recommend Nancy Duarte’s work, she’s brilliant and gives great advice on visuals and science communication in general. Another nice and comprehensive resource is „Building science graphics“ by Jen Christiansen. The other thing that helps a lot is to be a careful observer. Whenever studying a paper or listening to a presentation there is a lot to learn from paying attention to both the positive and negative outstanding aspects of the figures and illustrations.

I don’t really do dedicated practice sessions anymore, since every project I do is a form of practice in itself. At some point everything related to the craft becomes practice really, from doodling around during a train ride to watching a design documentary after a long day of work.

Patricia: In my case, I create my illustrations in 3D. During my PhD, I discovered a software called Blender, which became a game-changer for me. Blender is free and has a lot of online tutorials, which made it accessible to everyone. Through it, I found a new hobby where I could develop 3D models, perspective, lighting, and compositions, boosting my creativity. However, the beginning can be frustrating, but it gets better over time. Even after seven years of using it, I still have a lot to learn.

As Philipp mentioned, it’s not just about technical skills, having a visual sense is also crucial. I tried to develop this by following different artists and watching tutorials about design. But balancing my PhD with learning from YouTube tutorials was overwhelming. I realized I needed formal education and feedback to be more effective in my learning process. So, I enrolled in a 2-year online course on 3D animation and video games. This course taught me various skills useful not only for illustration but also for animation and even video game design. This additional knowledge allowed me to create interactive experiences, like science-based video games, which was an unexpected but exciting outcome.

Regarding practice, I currently have limited time for it. However, like Philipp, I approach each new project as a challenge and an opportunity to learn new skills. At the same time, I am very curious and love to jump from one tool to another, even if I cannot master everything. Trying new tools stimulates my creativity.

Joana: When I started getting interested in this field, going back to university full-time was not possible. On top of that, many courses out there focused almost exclusively on traditional techniques that emulate an old naturalistic illustration style. I really love that style, but it was not really what I was looking to learn. At the time, I was really curious to learn digital techniques from contemporary illustrators. That prompted me to look for short, after-work training opportunities to start developing my skills in that direction.

Picking up on Patricia and Philipp’s points, I also think a big part of our job depends on how we develop our visual sense, or visual taste. Curating our taste can determine who we choose as professional role models, what we collect as references and sources of inspiration, and how we analyze the work we see out there. One thing that also steers my direction is a frequent exposure to the work of artists that don’t have a heavy scientific background. Getting out of my usual bubble is often transformative for me.

Regarding practice, I think it’s important to keep devoting time to it, especially without the pressure to deliver. Certainly, tailoring what we learn in response to the projects we take on is crucial to develop new skills. But there is a particular aspect of professional growth that happens when we let ourselves just explore things for fun. It’s easy to stagnate once we start grinding through projects and focusing on results only. Occasional practice sessions are very helpful to push these dynamics back into an equilibrium that works for me.

Ubiquitin Graffiti by Philipp Dexheimer, which you can find in Vienna. © Philipp Dexheimer

Which is a lesson you learned, that has helped you the most in your job?

Patricia Bondia works as a scientific visual communicator since 2020. She holds a PhD in Biophysics. Her favourite artstyle is currently cinematic. Find out more on her website.

Patricia: I might get a bit philosophical with this question, but I think one of the key lessons I’ve learned is understanding that we are multi-potential individuals. During my journey, I discovered that exploring different interests and developing new skills, even those unrelated to my current career, is not a waste of time but an essential part of personal and professional growth. By exploring different hobbies, I found I was good at creating visuals. Combining this with my scientific knowledge, I explored a new part of myself and crafted a profession that truly fits me.

This experience taught me that learning isn’t compartmentalized like subjects in school. Instead, it’s deeply interconnected. Each new skill and piece of knowledge enhances others. This realization encouraged me to continue dedicating time to discovering new activities like diving or dance. It also increased my confidence that if I ever decide to shift careers or need to adapt to new circumstances, the diverse skills and experiences I’ve accumulated will support my success.

Joana: Such a great answer, Patricia. I couldn’t agree more!

I would add learning to build and nurture my professional network (always a work in progress). This can sound a bit repetitive, since there is likely no discussion about careers nowadays that doesn’t mention networking. But, in my case, I really feel the benefit of it.

From a career point of view, I think a good network is likelier to open doors for you that wouldn’t have opened otherwise. It brings you opportunities that push you out of your comfort zone, and encourage you to keep expanding as a professional. From a business point of view, our network can be a great source of recommendations, and recommendations, in turn, are key to ensure business sustainability. And of course, from a creativity point of view, feeling supported makes it a lot easier to stay motivated. Without motivation, my creativity can suffer and so does the work I can deliver. So, yes, nurture those connections! They play a bigger role than we usually assume.

Philipp: Love both of your answers Patricia & Joana, I actually had to think quite a bit about what to add. One more thought from my side:

One important lesson for me was the importance of technical fearlessness. By this I mean to not shy away from challenges that require finding new solutions to new creative problems. Often I had ideas for artwork which I initially deemed not feasible, however, with enough motivation one can always find a way. Over time this mindset drastically expands the personal skillset and is a great way to develop into a versatile artist.

Visual of an animation done by Patricia showing how light-activated molecules function © Patricia Bondia

Do you have anything else you want to share, that somebody interested in your profession should know?

Philipp: Do your own thing and follow your intuition, instead of looking too much at what’s out there already and attempting to replicate it. Be bold & enrich the world by creating a unique perspective on scientific phenomena in your very personal style.

Joana: I would add being aware of the impact of your visualizations and finding methodologies to evaluate that in a systematic way. Not just at the end of each project, but throughout. Ask questions and collect data that improves your practice through time, and ensures the work you produce fulfills its designated function as well as possible.

Patricia: I completely agree with Phillipp and Joana’s points. I’d like to add that I recommend the use of social media to build an online presence. In my experience, it can attract potential clients who appreciate your style and expertise.

Additionally, it is an excellent way to connect with other professionals in the field. It can be very helpful to ask questions or seek advice, especially when you’re starting out.

Thank you all for sharing your wonderful insights!

And this is it! We hope you enjoyed the read and can use some of the shared knowledge and experiences for your own career path. It’s incredible to see, that while all of our interviewees are working the same profession, the path that led there was different for each of them. There is not the one right way. So if you are starting from a different place, that’s okay. Find your own way. The important thing is to start.

If you are new to our blog, we, the Biologenkompass, are a german career blog for biologists. We have a few articles translated, although most of our content is in german. But Google Translate does a great job, so if you want to view our other articles, switch to our german page here. If you speak german and don’t want to miss any new content, don’t forget to follow us on Instagram or LinkedIn.

1 thoughts on “Viewpoints: Scientific Illustrator”